There is a real community theater, backyard cinema earnestness to Cyan’s Myst games, beginning from Myst, in which founding developer brothers Rand Miller and Robyn Miller played all characters themselves in full-motion video. Cyan is famed for its use of FMV in its games, but even after Myst and Riven became blockbusters, the closest the Myst franchise has ever gotten to having a famous actor has been Brad Dourif’s (The Lord of the Rings) turn as the villain in Myst 3: Exile — which he got not from a casting call but because he was a fan of the series.

Check out our special issue Polygon FM, a week of stories about all the places where music and games connect — retrospectives, interviews, and much more.

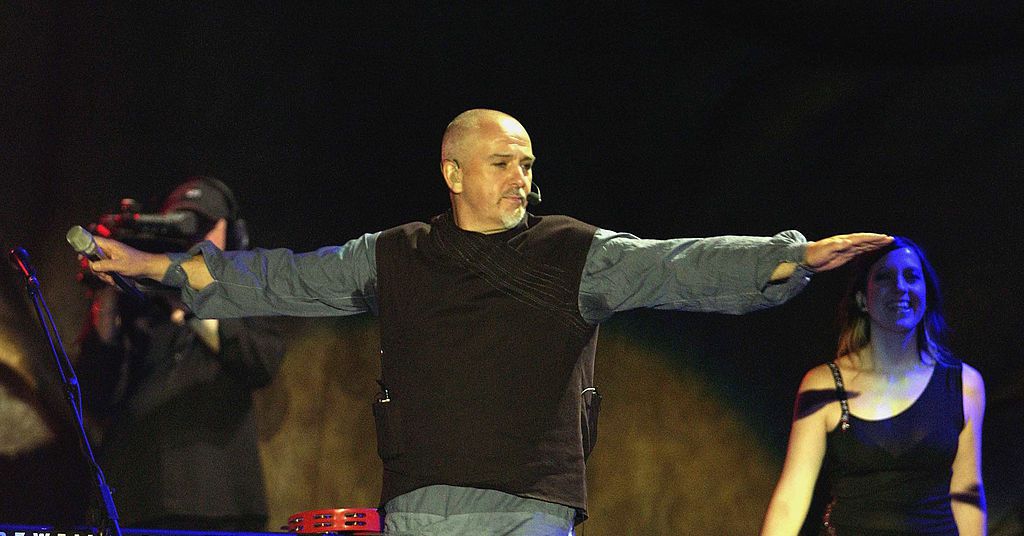

But there is one big celebrity moment in the Myst franchise that is also the most staggering musical choice I’ve ever experienced in a video game: Myst 4: Revelation’s Unskippable Peter Gabriel Cutscene.

On paper, there’s nothing good about the Unskippable Peter Gabriel Cutscene. For example, it’s unskippable. Furthermore, it comes out of left field — Myst, the steampunky FMV puzzle adventure series, is emphatically not a “voiced, English-language pop song interlude” kind of franchise. The cutscene’s visuals, while clearly a work of bespoke animation, are full of so many shapes spiraling out from center screen that it’s unavoidably reminiscent of a Winamp visualization. And it all leads to maybe the worst puzzle ever put in a Myst game.

And yet… I unironically love the Unskippable Peter Gabriel Winamp Cutscene. Because of the joy of theater.

Peter Gabriel, in a truly obscure Myst game? you may be asking. Peter Gabriel, the prog rock frontman, world music advocate, crusading human rights activist — you know, “In Your Eyes”? That Peter Gabriel? How?!

Well, in the 1990s, Peter Gabriel got… really into CD-ROMs. He produced two interactive musical experiences/games, Xplora1: Peter Gabriel’s Secret World and Peter Gabriel: Eve. And if you were a person in the 1990s who was interested in the possibilities of CD-ROM technology, you were a person who played Myst and Riven.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25564550/MV5BYzlhYzIxNWItY2RmOC00YjFjLTgzYzktOGViNDk5MjU5Yjk4XkEyXkFqcGdeQXVyMTQzMjU1NjE_._V1_.jpg)

Image: Real World Media/MacPlay

Which is to say, just like Dourif, Gabriel was a fan.

“When Myst came out I thought it succeeded well in creating a feeling of other worlds in which mystery and imagination were the compelling elements instead of the usual action-packed ‘shoot ‘em ups’,” Gabriel said in a 2004 IGN article. “I think there is some similarity with the way I try and create worlds of sound. I very much enjoyed working on Myst IV Revelation.”

Myst 4 was always going to be a weird entry in the series, made during a period when Ubisoft — hard at work producing mainstream games like Splinter Cell and Prince of Persia — held the rights to the franchise. Narratively a direct sequel to Myst, it was the first time Ubisoft Montreal had ever made an adventure game with pre-rendered graphics, and that shift was apparently a real grind. The end result was a fascinatingly hybrid product. A bespoke game engine delivered pre-rendered images with animated wind and water, and real-time features like lens flares and focal depth, making Myst 4 the most cinematic and immersive game in the franchise. Yet the game still had over an hour of FMV in it, with live-action, costumed actors playing the characters.

The thrust of the game’s story begins when Sirrus and Achenar (Atrus’ wayward large adult sons, who were each imprisoned in a different alternate world, or Age, at the close of Myst) break out and kidnap their much younger sister Yeesha. It’s on you to explore their prison worlds and confront them in a final Age, Serenia, where Myst 4 becomes not just a weird entry in the series but a really, really interesting one.

If the Myst games have a cohesive mechanic, it’s puzzle anthropology — the clues to the puzzles lie in accounts and cultural artifacts from alternate worlds, usually ones that have been exploited and ruined by Atrus’ awful family members. Myst 4 is the first game in the series that not only has something more complicated to say than “Don’t do a colonialism” (instead, Myst 4 is about prison reform, but that’s another essay) — it also actually practices what the franchise preaches.

Serenia is the first time where the culture you study is not separated from the people who belong to it. In contrast to previous games, native inhabitants not only appear but are unafraid of you, speak to you in a language you understand, and personally welcome you into their most sacred practices. There are definitely still some The natives of this land, so in tune with nature, so wise stereotypes going on here, but for a Myst game this is a stratospheric leap of evolution.

Your search for answers eventually leads you to the priesthood of Serenia, who offer to help you find what you seek in their sacred Dream realm, guided by your own personal elemental spirit (The natives of this land, so in tune with nature, so wise). A robed priestess leads you to the sacred chamber. At her direction you lie on the stone slab, and she positions a carved stone above you with two holes representing “the eyes of the Ancestors.” As she delivers her final instructions, soothing but boppable music begins to play, soft percussion and high synths. And then, as you start to trip…

…Peter Gabriel starts singing about curtains.

Congratulations: You have reached the Unskippable Peter Gabriel Cutscene, featuring a roughly three-minute cut of “Curtains,” originally the B-side of his 1986 single “Big Time.” Things do not get less weird from here!

Once the cutscene finishes, your spirit guide, in the form of Peter Gabriel’s disembodied voice, introduces you to… a color flip puzzle. You’re surrounded by colored balls, and you have to get all the balls to turn white (“Lend the ancestors your energy” or something). If the game deems the way you touch the balls to be too erratic, it will play a disapproving sound, and a bunch of the colored balls will randomize.

Not only that, but this color flip puzzle is a bottleneck. If you’ve gotten there, it’s likely because you’ve completed all else that’s possible. Until you get past it, this is the whole game. Not a machine to intuit, a notebook to peruse, or a numerical system to decipher. A tone-setting cutscene featuring a Peter Gabriel jam and then Peter Gabriel ASMR with colored balls.

It’s tonal nonsense. It’s against the core puzzle philosophies of the franchise. It’s an enormous swing that doesn’t work. And I still love it, because Myst games are — hear me out — kind of like theater.

Even though these are not role-playing games, Cyan has imbued the franchise with an invitation to the player to participate in constructing the game’s reality. Myst and Riven begin with earnest notes advising you to put on the best pair of stereo headphones you have, to dim your room lights, and to calibrate your screen and audio just so for the best immersion that 1990s computer gaming can provide. Cyan also maintains a charming kayfabe with its community, in which the Myst franchise is based on real events, derived from archaeological findings in the southwest United States and the personal history of Atrus’ family.

These attempts to preserve the reality of Myst only frame how imperfect that illusion is. The seams are here before you: the amateur performers, the limits of exploration in a pre-rendered 2D environment, the long animations to wait through, the live-action footage superimposed on digital environments. Myst games ask for your patience — with frustrating puzzles and by making you wait — and they ask you to buy into their reality, because a tiny independent studio like Cyan can’t make a perfectly convincing illusion on its own.

In that context, what is the “Curtains” cutscene and Peter Gabriel’s (honestly really quite good) acting stint as the player’s spirit guide? It’s inviting a fan up on the stage to contribute to the thing they love. On a stage, all the seams are visible: the lines of the trap door, the microphones taped to the actors’ cheeks, the rather Winamp-reminiscent animation, the out-of-left-field song, and the stupid color matching puzzle.

But you complete the circuit with your own mind, and the stage becomes another reality instead of a platform for people reciting lines. Myst 4’s Unskippable Peter Gabriel Cutscene is made entirely of really visible seams. But it also feels like an earnest creative choice from someone who’s personally invested in the work.

Rand Miller, who maintains that he strongly dislikes acting, played Atrus in Myst from efficiency and necessity. And he’s been stuck reprising his amateur performance ever since, because fans wouldn’t have it any other way. It simply wouldn’t be Atrus without the awkward vibes! And if I’m here for Rand Miller’s Atrus, how can I turn up my nose at Peter Gabriel’s spirit guidance? How can I love Myst games and not love their biggest risks? I’m already lying on the stone slab. It’s not hard at all to complete the circuit with my mind and have a chill time flying around this Winamp visualization while a boppable song plays. This is the Zen of Myst games.

That said, the color puzzle still blows.